Design

NOTE: for accompanying visual illustration see this slide deck.

NSQ is a successor to simplequeue (part of simplehttp) and as such is designed to (in no particular order):

- support topologies that enable high-availability and eliminate SPOFs

- address the need for stronger message delivery guarantees

- bound the memory footprint of a single process (by persisting some messages to disk)

- greatly simplify configuration requirements for producers and consumers

- provide a straightforward upgrade path

- improve efficiency

Simplifying Configuration and Administration

A single nsqd instance is designed to handle multiple streams of data at once. Streams are called

“topics” and a topic has 1 or more “channels”. Each channel receives a copy of all the

messages for a topic. In practice, a channel maps to a downstream service consuming a topic.

Topics and channels are not configured a priori. Topics are created on first use by publishing to the named topic or by subscribing to a channel on the named topic. Channels are created on first use by subscribing to the named channel.

Topics and channels all buffer data independently of each other, preventing a slow consumer from causing a backlog for other channels (the same applies at the topic level).

A channel can, and generally does, have multiple clients connected. Assuming all connected clients are in a state where they are ready to receive messages, each message will be delivered to a random client (when topology aware consumption is enabled, messages will be delivered at random but with priority based on closest geographical client(s), see Topology Aware Consumption). For example:

To summarize, messages are multicast from topic -> channel (every channel receives a copy of all messages for that topic) but evenly distributed from channel -> consumers (each consumer receives a portion of the messages for that channel).

NSQ also includes a helper application, nsqlookupd, which provides a directory service where

consumers can lookup the addresses of nsqd instances that provide the topics they are interested

in subscribing to. In terms of configuration, this decouples the consumers from the producers (they

both individually only need to know where to contact common instances of nsqlookupd, never each

other), reducing complexity and maintenance.

At a lower level each nsqd has a long-lived TCP connection to nsqlookupd over which it

periodically pushes its state. This data is used to inform which nsqd addresses nsqlookupd will

give to consumers. For consumers, an HTTP /lookup endpoint is exposed for polling.

To introduce a new distinct consumer of a topic, simply start up an NSQ client configured with

the addresses of your nsqlookupd instances. There are no configuration changes needed to add

either new consumers or new publishers, greatly reducing overhead and complexity.

NOTE: in future versions, the heuristic nsqlookupd uses to return addresses could be based on

depth, number of connected clients, or other “intelligent” strategies. The current implementation is

simply all. Ultimately, the goal is to ensure that all producers are being read from such that

depth stays near zero.

It is important to note that the nsqd and nsqlookupd daemons are designed to operate

independently, without communication or coordination between siblings.

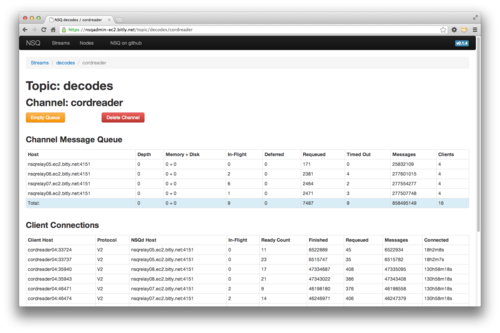

We also think that it’s really important to have a way to view, introspect, and manage the

cluster in aggregate. We built nsqadmin to do this. It provides a web UI to browse the hierarchy

of topics/channels/consumers and inspect depth and other key statistics for each layer. Additionally

it supports a few administrative commands such as removing and emptying a channel (which is a useful

tool when messages in a channel can be safely thrown away in order to bring depth back to 0).

Straightforward Upgrade Path

This was one of our highest priorities. Our production systems handle a large volume of traffic, all built upon our existing messaging tools, so we needed a way to slowly and methodically upgrade specific parts of our infrastructure with little to no impact.

First, on the message producer side we built nsqd to match simplequeue.

Specifically, nsqd exposes an HTTP /pub endpoint, just like simplequeue, to POST binary data

(with the one caveat that the endpoint takes an additional query parameter specifying the “topic”).

Services that wanted to switch to start publishing to nsqd only have to make minor code changes.

Second, we built libraries in both Python and Go that matched the functionality and idioms we had been accustomed to in our existing libraries. This eased the transition on the message consumer side by limiting the code changes to bootstrapping. All business logic remained the same.

Finally, we built utilities to glue old and new components together. These are all available in the

examples directory in the repository:

nsq_to_file- durably write all messages for a given topic to a filensq_to_http- perform HTTP requests for all messages in a topic to (multiple) endpoints

Eliminating SPOFs

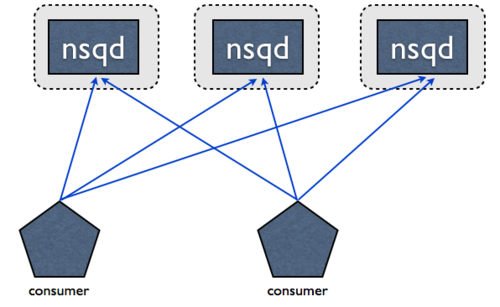

NSQ is designed to be used in a distributed fashion. nsqd clients are connected (over TCP) to

all instances providing the specified topic. There are no middle-men, no message brokers, and no

SPOFs:

This topology eliminates the need to chain single, aggregated, feeds. Instead you consume directly from all producers. Technically, it doesn’t matter which client connects to which NSQ, as long as there are enough clients connected to all producers to satisfy the volume of messages, you’re guaranteed that all will eventually be processed.

For nsqlookupd, high availability is achieved by running multiple instances. They don’t

communicate directly to each other and data is considered eventually consistent. Consumers poll

all of their configured nsqlookupd instances and union the responses. Stale, inaccessible, or

otherwise faulty nodes don’t grind the system to a halt.

Message Delivery Guarantees

NSQ guarantees that a message will be delivered at least once, though duplicate messages are possible. Consumers should expect this and de-dupe or perform idempotent operations.

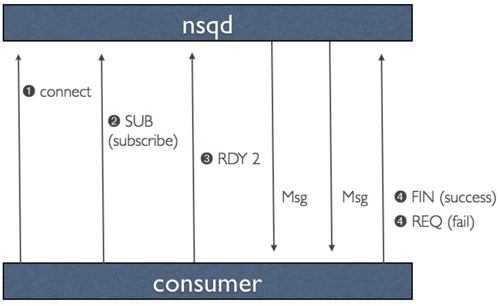

This guarantee is enforced as part of the protocol and works as follows (assume the client has successfully connected and subscribed to a topic):

- client indicates they are ready to receive messages

- NSQ sends a message and temporarily stores the data locally (in the event of re-queue or timeout)

- client replies FIN (finish) or REQ (re-queue) indicating success or failure respectively. If client does not reply NSQ will timeout after a configurable duration and automatically re-queue the message)

This ensures that the only edge case that would result in message loss is an unclean shutdown of an

nsqd process. In that case, any messages that were in memory (or any buffered writes not flushed

to disk) would be lost.

If preventing message loss is of the utmost importance, even this edge case can be mitigated. One

solution is to stand up redundant nsqd pairs (on separate hosts) that receive copies of the same

portion of messages. Because you’ve written your consumers to be idempotent, doing double-time on

these messages has no downstream impact and allows the system to endure any single node failure

without losing messages.

The takeaway is that NSQ provides the building blocks to support a variety of production use cases and configurable degrees of durability.

Bounded Memory Footprint

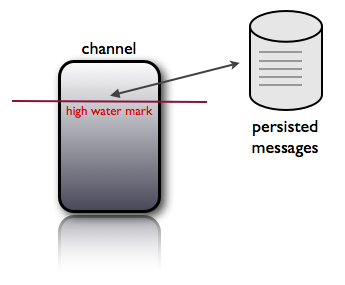

nsqd provides a configuration option --mem-queue-size that will determine the number of messages

that are kept in memory for a given queue. If the depth of a queue exceeds this threshold messages

are transparently written to disk. This bounds the memory footprint of a given nsqd process to

mem-queue-size * #_of_channels_and_topics:

Also, an astute observer might have identified that this is a convenient way to gain an even higher guarantee of delivery by setting this value to something low (like 1 or even 0). The disk-backed queue is designed to survive unclean restarts (although messages might be delivered twice).

Also, related to message delivery guarantees, clean shutdowns (by sending a nsqd process the

TERM signal) safely persist the messages currently in memory, in-flight, deferred, and in various

internal buffers.

Note, a topic/channel whose name ends in the string #ephemeral will not be buffered to disk and

will instead drop messages after passing the mem-queue-size. This enables consumers which do not

need message guarantees to subscribe to a channel. These ephemeral channels will also disappear

after its last client disconnects. For an ephemeral topic, this implies that at least one channel

has been created, consumed, and deleted (typically an ephemeral channel).

Efficiency

NSQ was designed to communicate over a “memcached-like” command protocol with simple size-prefixed responses. All message data is kept in the core including metadata like number of attempts, timestamps, etc. This eliminates the copying of data back and forth from server to client, an inherent property of the previous toolchain when re-queueing a message. This also simplifies clients as they no longer need to be responsible for maintaining message state.

Also, by reducing configuration complexity, setup and development time is greatly reduced (especially in cases where there are >1 consumers of a topic).

For the data protocol, we made a key design decision that maximizes performance and throughput by

pushing data to the client instead of waiting for it to pull. This concept, which we

call RDY state, is essentially a form of client-side flow control.

When a client connects to nsqd and subscribes to a channel it is placed in a RDY state of 0.

This means that no messages will be sent to the client. When a client is ready to receive messages

it sends a command that updates its RDY state to some # it is prepared to handle, say 100. Without

any additional commands, 100 messages will be pushed to the client as they are available (each time

decrementing the server-side RDY count for that client).

Client libraries are designed to send a command to update RDY count when it reaches ~25% of the

configurable max-in-flight setting (and properly account for connections to multiple nsqd

instances, dividing appropriately).

This is a significant performance knob as some downstream systems are able to more-easily batch

process messages and benefit greatly from a higher max-in-flight.

Notably, because it is both buffered and push based with the ability to satisfy the need for

independent copies of streams (channels), we’ve produced a daemon that behaves like simplequeue

and pubsub combined . This is powerful in terms of simplifying the topology of our systems where

we would have traditionally maintained the older toolchain discussed above.

Topology Aware Consumption

nsqd provides a configuration option --enable-experiments that can be used to enable the topology-aware-consumption functionality. If this experiment is turned on and configurations are also provided for --topology-region and --topology-zone, the nsqd will push messages to consumers based on a topology-aware behavior pattern.

Consumers can provide their own topology region and zone via options set in their IDENTIFY message to the nsqd host. If this information is not provided, the consumer will be considered to be outside of both the zone and region of the nsqd.

When configured, nsqd will prioritize the pushing of messages to consumers based on those that are geographically closest to them. It will prioritize first pushing messages to consumers within the same region and zone if possible, then pushing messages to consumers within the same region, and lastly will fall back to pushing to any consumer possible at random (regular behavior).

This behiavor pattern allows for running nsqd in a multiregion application architecture, and to minimize network egress costs for nsqd interacting with consumers in different geolocations.

Go

We made a strategic decision early on to build the NSQ core in Go. We recently blogged about our use of Go at bitly and alluded to this very project - it might be helpful to browse through that post to get an understanding of our thinking with respect to the language.

Regarding NSQ, Go channels (not to be confused with NSQ channels) and the language’s built

in concurrency features are a perfect fit for the internal workings of nsqd. We leverage buffered

channels to manage our in memory message queues and seamlessly write overflow to disk.

The standard library makes it easy to write the networking layer and client code. The built in memory and cpu profiling hooks highlight opportunities for optimization and require very little effort to integrate. We also found it really easy to test components in isolation, mock types using interfaces, and iteratively build functionality.