Topology Patterns

This document describes some NSQ patterns that solve a variety of common problems.

DISCLAIMER: there are some obvious technology suggestions but this document

generally ignores the deeply personal details of choosing proper tools, getting

software installed on production machines, managing what service is running

where, service configuration, and managing running processes (daemontools,

supervisord, init.d, etc.).

Metrics Collection

Regardless of the type of web service you’re building, in most cases you’re going to want to collect some form of metrics in order to understand your infrastructure, your users, or your business.

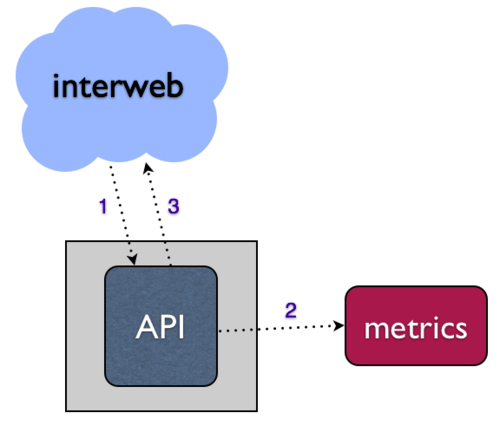

For a web service, most often these metrics are produced by events that happen via HTTP requests, like an API. The naive approach would be to structure this synchronously, writing to your metrics system directly in the API request handler.

- What happens when your metrics system goes down?

- Do your API requests hang and/or fail?

- How will you handle the scaling challenge of increasing API request volume or breadth of metrics collection?

One way to resolve all of these issues is to somehow perform the work of writing into your metrics system asynchronously - that is, place the data in some sort of local queue and write into your downstream system via some other process (consuming that queue). This separation of concerns allows the system to be more robust and fault tolerant. At bitly, we use NSQ to achieve this.

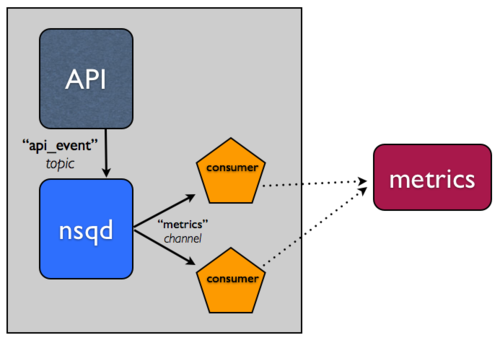

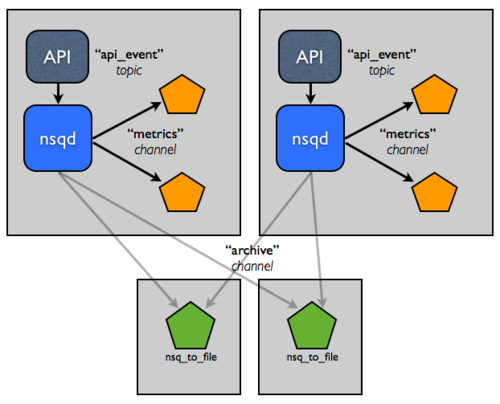

Brief tangent: NSQ has the concept of topics and channels. Basically, think of a topic as a unique stream of messages (like our stream of API events above). Think of a channel as a copy of that stream of messages for a given set of consumers. Topics and channels are both independent queues, too. These properties enable NSQ to support both multicast (a topic copying each message to N channels) and distributed (a channel equally dividing its messages among N consumers) message delivery.

For a more thorough treatment of these concepts, read through the design doc and slides from our Golang NYC talk, specifically slides 19 through 33 describe topics and channels in detail.

Integrating NSQ is straightforward, let’s take the simple case:

- Run an instance of

nsqdon the same host that runs your API application. - Update your API application to write to the local

nsqdinstance to queue events, instead of directly into the metrics system. To be able to easily introspect and manipulate the stream, we generally format this type of data in line-oriented JSON. Writing intonsqdcan be as simple as performing an HTTP POST request to the/putendpoint. - Create a consumer in your preferred language using one of our

client libraries. This “worker” will subscribe to the

stream of data and process the events, writing into your metrics system.

It can also run locally on the host running both your API application

and

nsqd.

Here’s an example worker written with our official Python client library:

In addition to de-coupling, by using one of our official client libraries, consumers will degrade gracefully when message processing fails. Our libraries have two key features that help with this:

- Retries - when your message handler indicates failure, that information is

sent to

nsqdin the form of aREQ(re-queue) command. Also,nsqdwill automatically time out (and re-queue) a message if it hasn’t been responded to in a configurable time window. These two properties are critical to providing a delivery guarantee. - Exponential Backoff - when message processing fails the reader library will delay the receipt of additional messages for a duration that scales exponentially based on the # of consecutive failures. The opposite sequence happens when a reader is in a backoff state and begins to process successfully, until 0.

In concert, these two features allow the system to respond gracefully to downstream failure, automagically.

Persistence

Ok, great, now you have the ability to withstand a situation where your metrics system is unavailable with no data loss and no degraded API service to other endpoints. You also have the ability to scale the processing of this stream horizontally by adding more worker instances to consume from the same channel.

But, it’s kinda hard ahead of time to think of all the types of metrics you might want to collect for a given API event.

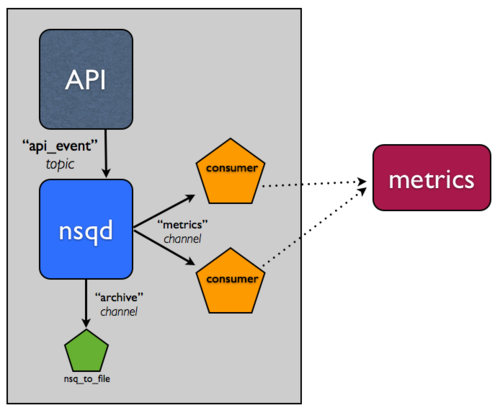

Wouldn’t it be nice to have an archived log of this data stream for any future operation to leverage? Logs tend to be relatively easy to redundantly backup, making it a “plan z” of sorts in the event of catastrophic downstream data loss. But, would you want this same consumer to also have the responsibility of archiving the message data? Probably not, because of that whole “separation of concerns” thing.

Archiving an NSQ topic is such a common pattern that we built a utility, nsq_to_file, packaged with NSQ, that does exactly what you need.

Remember, in NSQ, each channel of a topic is independent and receives a

copy of all the messages. You can use this to your advantage when archiving

the stream by doing so over a new channel, archive. Practically, this means

that if your metrics system is having issues and the metrics channel gets

backed up, it won’t effect the separate archive channel you’ll be using to

persist messages to disk.

So, add an instance of nsq_to_file to the same host and use a command line

like the following:

/usr/local/bin/nsq_to_file --nsqd-tcp-address=127.0.0.1:4150 --topic=api_requests --channel=archive

Distributed Systems

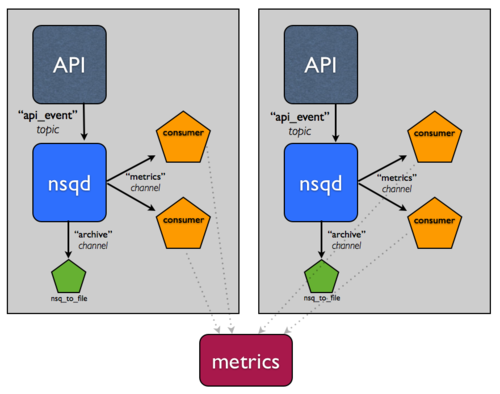

You’ll notice that the system has not yet evolved beyond a single production host, which is a glaring single point of failure.

Unfortunately, building a distributed system is hard. Fortunately, NSQ can help. The following changes demonstrate how NSQ alleviates some of the pain points of building distributed systems as well as how its design helps achieve high availability and fault tolerance.

Let’s assume for a second that this event stream is really important. You want to be able to tolerate host failures and continue to ensure that messages are at least archived, so you add another host.

Assuming you have some sort of load balancer in front of these two hosts you can now tolerate any single host failure.

Now, let’s say the process of persisting, compressing, and transferring these logs is affecting performance. How about splitting that responsibility off to a tier of hosts that have higher IO capacity?

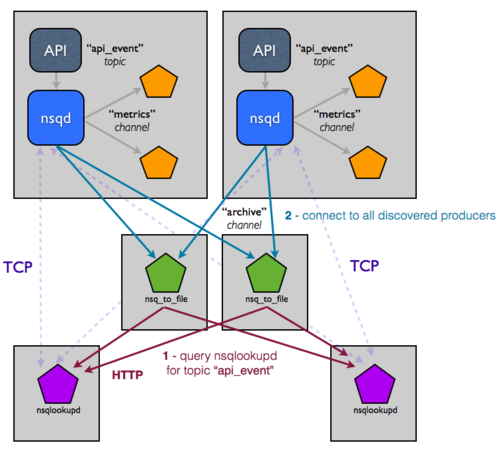

This topology and configuration can easily scale to double-digit hosts, but

you’re still managing configuration of these services manually, which does not

scale. Specifically, in each consumer, this setup is hard-coding the address

of where nsqd instances live, which is a pain. What you really want is for

the configuration to evolve and be accessed at runtime based on the state of

the NSQ cluster. This is exactly what we built nsqlookupd to

address.

nsqlookupd is a daemon that records and disseminates the state of an NSQ

cluster at runtime. nsqd instances maintain persistent TCP connections to

nsqlookupd and push state changes across the wire. Specifically, an nsqd

registers itself as a producer for a given topic as well as all channels it

knows about. This allows consumers to query an nsqlookupd to determine who

the producers are for a topic of interest, rather than hard-coding that

configuration. Over time, they will learn about the existence of new

producers and be able to route around failures.

The only changes you need to make are to point your existing nsqd and

consumer instances at nsqlookupd (everyone explicitly knows where

nsqlookupd instances are but consumers don’t explicitly know where

producers are, and vice versa). The topology now looks like this:

At first glance this may look more complicated. It’s deceptive though, as

the effect this has on a growing infrastructure is hard to communicate

visually. You’ve effectively decoupled producers from consumers because

nsqlookupd is now acting as a directory service in between. Adding

additional downstream services that depend on a given stream is trivial, just

specify the topic you’re interested in (producers will be discovered by

querying nsqlookupd).

But what about availability and consistency of the lookup data? We generally

recommend basing your decision on how many to run in congruence with your

desired availability requirements. nsqlookupd is not resource intensive and

can be easily homed with other services. Also, nsqlookupd instances do not

need to coordinate or otherwise be consistent with each other. Consumers will

generally only require one nsqlookupd to be available with the information

they need (and they will union the responses from all of the nsqlookupd

instances they know about). Operationally, this makes it easy to migrate to a

new set of nsqlookupd.